Page 11 - 4859_BedfordLife

P. 11

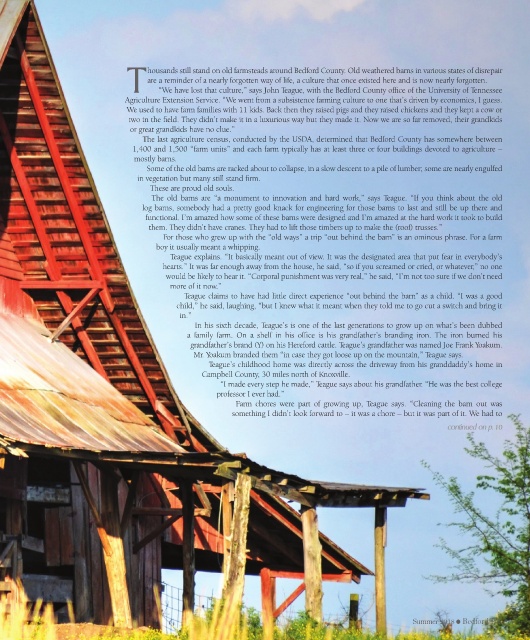

T housands still stand on old farmsteads around Bedford County. Old weathered barns in various states of disrepair

are a reminder of a nearly forgotten way of life, a culture that once existed here and is now nearly forgotten.

“We have lost that culture,” says John Teague, with the Bedford County office of the University of Tennessee

Agriculture Extension Service. “We went from a subsistence farming culture to one that’s driven by economics, I guess.

We used to have farm families with 11 kids. Back then they raised pigs and they raised chickens and they kept a cow or

two in the field. They didn’t make it in a luxurious way but they made it. Now we are so far removed, their grandkids

or great grandkids have no clue.”

The last agriculture census, conducted by the USDA, determined that Bedford County has somewhere between

1,400 and 1,500 “farm units” and each farm typically has at least three or four buildings devoted to agriculture –

mostly barns.

Some of the old barns are racked about to collapse, in a slow descent to a pile of lumber; some are nearly engulfed

in vegetation but many still stand firm.

These are proud old souls.

The old barns are “a monument to innovation and hard work,” says Teague. “If you think about the old

log barns, somebody had a pretty good knack for engineering for those barns to last and still be up there and

functional. I’m amazed how some of these barns were designed and I’m amazed at the hard work it took to build

them. They didn’t have cranes. They had to lift those timbers up to make the (roof) trusses.”

For those who grew up with the “old ways” a trip “out behind the barn” is an ominous phrase. For a farm

boy it usually meant a whipping.

Teague explains. “It basically meant out of view. It was the designated area that put fear in everybody’s

hearts.” It was far enough away from the house, he said, “so if you screamed or cried, or whatever,” no one

would be likely to hear it. “Corporal punishment was very real,” he said, “I’m not too sure if we don’t need

more of it now.”

Teague claims to have had little direct experience “out behind the barn” as a child. “I was a good

child,” he said, laughing, “but I knew what it meant when they told me to go cut a switch and bring it

in.”

In his sixth decade, Teague’s is one of the last generations to grow up on what’s been dubbed

a family farm. On a shelf in his office is his grandfather’s branding iron. The iron burned his

grandfather’s brand (Y) on his Hereford cattle. Teague’s grandfather was named Joe Frank Yoakum.

Mr. Yoakum branded them “in case they got loose up on the mountain,” Teague says.

Teague’s childhood home was directly across the driveway from his granddaddy’s home in

Campbell County, 30 miles north of Knoxville.

“I made every step he made,” Teague says about his grandfather. “He was the best college

professor I ever had.”

Farm chores were part of growing up, Teague says. “Cleaning the barn out was

something I didn’t look forward to – it was a chore – but it was part of it. We had to

continued on p. 10

Summer 2018 l Bedford Life 9